The term ocular hypertension usually refers to any situation in which the pressure inside the eye, called intraocular pressure, is higher than normal. Eye pressure is measured in millimeters of mercury (mm Hg). Normal eye pressure ranges from 10-21 mm Hg. Ocular hypertension is an eye pressure of greater than 21 mm Hg.

Ocular hypertension is a term that is used to describe individuals who should be observed more closely than the general population for the onset of glaucoma. For this reason, another term to refer to a person with ocular hypertension is “glaucoma suspect,” or someone whom the eye doctor is concerned may have or may develop glaucoma because of elevated pressure inside the eyes.

Ocular hypertension is commonly defined as a condition with the following criteria:

- An intraocular pressure consistently higher than 21 mm Hg in one or both eyes at two or more clinic visits.

- There’s an absence of clinical signs of glaucoma, such as optic nerve damage

- No signs of glaucoma are evident on visual field testing, which is a test to assess your peripheral (or side) vision.

- To determine other possible causes for your high eye pressure, an eye doctor assesses whether your drainage system (called the “angle”) is open or closed. The angle is seen using a technique called gonioscopy. This technique involves the use of a special contact lens to examine the drainage angles (or channels) in your eyes to see if they are open, narrowed, or closed.

- No signs of any ocular disease are present. Some eye diseases can increase the pressure inside the eye.

WHAT CAUSES OCULAR HYPERTENSION?

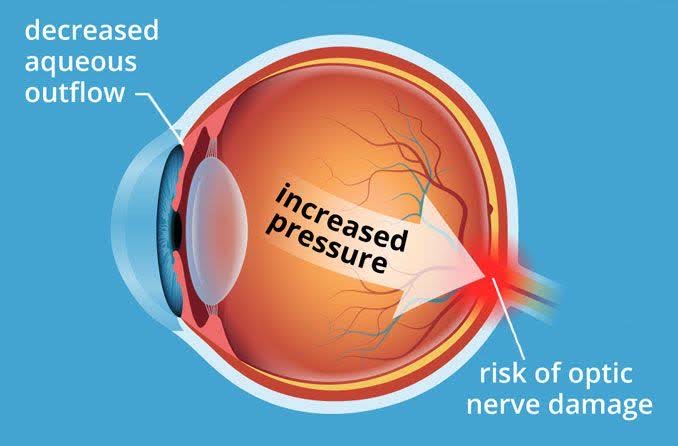

The eye constantly makes a clear fluid called aqueous humor, which enters the front section of the eye to supply nutrition. An equal amount of fluid also flows out simultaneously to maintain a normal eye pressure. When this drainage system fails to function properly, the fluid accumulates and intraocular pressure increases, leading to ocular hypertension.

In most cases, a blockage in the drainage channels of the eye or overproduction of aqueous humor is responsible for ocular hypertension. In addition, injuries to the eye or certain eye disorders can cause ocular hypertension. Certain medicines, such as steroids, can also elevate the intraocular pressure.

DOES OCULAR HYPERTENSION HAVE ANY SYMPTOMS?

Ocular hypertension typically doesn’t have any symptoms. Because of this, it’s common to have ocular hypertension and not be aware of it.

This is one of the reasons why regular eye exams are so important. Measuring your eye pressure is one of the tests your eye doctor will perform during a routine eye exam.

WHAT ARE THE RISK FACTORS FOR OCULAR HYPERTENSION?

Anyone can develop ocular hypertension. However, you may be at an increased risk if you:

- Have high blood pressure or diabetes

- Have a family history of ocular hypertension or glaucoma

- Are over the age of 40

- Are Black or Hispanic

- Have had eye surgery or an eye injury in the past

- Have taken long-term steroid medications

- Have certain eye conditions, including nearsightedness, pigment dispersion syndrome, and pseudoexfoliation syndrome

HOW IS OCULAR HYPERTENSION MANAGED?

Ocular hypertension is treated with prescription eye drops that can either help aqueous humor to drain from your eye or lower the amount of aqueous humor that your eye produces.

The eye doctor will schedule a follow-up appointment a few weeks later to see how the eye drops are working.

Additionally, since ocular hypertension increases the risk of glaucoma, it’s important to follow up with your eye doctor every 1 to 2 years for an eye exam.

If your intraocular pressure is only slightly elevated, your eye doctor may wish to continue to monitor it without the use of prescription eye drops. If it remains elevated or gets higher, they may then recommend prescription eye drops.

SURGERY FOR OCULAR HYPERTENSION

For some people, ocular hypertension may not respond well to eye drop medications. In this case, surgery may be recommended to help lower intraocular pressure.

The goal of surgery for ocular hypertension is to create an outlet that allows excess aqueous humor to drain from the eye. This can be accomplished using a laser or more traditional surgical techniques.